John Muir Trail, 1971, Preparation

In 1971 my younger brother Mike and I planned a 28 day trip on the JMT, with 12 people. Some people might be interested in our trip as a view into backpacking practices, philosophy, and technology in those days. Current travelers on the JMT have seriously lighter loads than we could accomplish in the 1970s, and they cover many more miles per day than we did, but one thing different about our trip was that we climbed 17 Sierra peaks, did a lot of fishing, and had layover days.

With no permits, stoves, water filters, bear canisters, GPS, iPods, etc., the 70's was a simpler time, but the beauty and allure of the Sierras remains an unchanging constant -- as it was in the day of John Muir, as it was to us in the 70's, as it is to hikers today. In 1971, me being 21 years old and my brother being 19, we were winging it on doing the JMT. MTR and VVR didn't exist as backpacker way stations, as far as we knew. There were no guide books, and the trails were not as well marked as they are today. We didn't mail food in buckets to Reds or Onion Valley, we had friends drive them up and we met at the trailheads. We had hiked from Cottonwood over New Army Pass to Symmes Creek in 1969, spending some timein the Wallace and Wales area and climbed some peaks. In 1970 we had hiked from Bishop Pass to Sawmill Pass, and had climbed some peaks there, notably North Palisade. But we had the most important things to succeed in such an endeavor: confidence and ignorance.

Our 1971 backpack of the John Muir Trail began as a two man trip, just my brother Mike and I. The closer we got to the planning state, the more we found other interested people. It reached five or six and we decided to make it a Y’s Hikers (YMCA) trip in order to be insured with the Y. Almost immediately we had a party of 12 or possibly 16. The extra four were Scouts, but when Mike refused to put them in one cook group they dropped out.

After weeks of preparation both individually and collectively, we left the Lancaster, Calif. YMCA on a Saturday morning with 12 hikers, full backpacks, and the greatest of expectations. The Powells helped transport the group up the Owen’s Valley, over Tioga Pass, and on to Tuolumne Meadows. On the way up, we took a break at Lone Pine to shuttle a car to Whitney Portal where it remain parked for 28 days (you could never get away with that today). If I remember, we had to stop a couple of times with one of the cars to pour water over the radiator because it got too hot going over Tioga Pass.

Once dropped off at Tuolumne Meadows, all we had to do was hike 227 miles through the roughest, highest, and most beautiful mountain country in the North American Continent.

Itinerary:

1. S Toulumne Meadows to Rafferty Creek

2. S Rafferty Creek to below Lyell Creek

3. M Lyell Creek, over Donahue and Island Pass, climbed Donahue Pk, to Thousand island Lake

4. T Layover Day

5. W Thousand Island Lake to below Lake Ediza

6. T layover day, climbed Ritter and Banner

7. F lake Ediza to Trinity Lakes

8. S to Devils Postpile, get food drop, hike 2 miles out of DP

9. S to Purple Lake

10. M over Silver Pass, to Quail Meadow

11. T to Lake Marie

12. W over Selmer Pass to Evolution Valley

13. T over Shit for Brains Pass, to Midnight Lake

14. F to Lake Sabrina, get ride to South Lake

15. S to Saddlerock Lake below Bishop Pass, climbed Mt.Agassiz from Bishop Pass

16. S To Barrett lakes

17. M layover, climbed Polomonium, Mt. Sill,

18. T to Palisade Lake

19. W over Mather Pass to Lake Marjorie, climbed Split

20. Y: over Pinchot Pass to Rae lakes

21. F To Onion Valley, over Glen, Kearsarge

22. S to Flower Lake

23. S over Kearsearge Pass to Bubbs Creek, climbed University Pk.

24. M over Forester Pass to Wright lakes

25. T Layover, climbed Russell, Constitution, Tunnabora, Bernard

26. W another layover for Group A, climbed more peaks, to Wallace lakes for Group B

27. T To Hitchcock lake for Group A, layover at Wallace Lake for Group B

28. F over Trail Crest to the Portal, group B spent the night on top of Whitney

29. S group B down to Whitney Portal

This is a letter from Mike to me when I was still off at college, and he was in Lancaster starting to get things organized.

Bob:

Here’s the signup $50 paid:

Kevin Anderson; me; John Laine; $10 deposit Chris Hughes;Robert Bouclin; Tomlinson (age 14 but really wants to go and went on shakedown hike); Lowry, Conrad; You; Wes Little; and Madeline Payne (ah yes, Gordon’s has put in a mountaineering line. Wipe out for Eaton! Wally to help buy food wholesale. Cheep. Good equipment. The jacket sold for $25 at last meeting to Payne); and Antonia Reeves

Plus two kids who want to wait until an Explorer Scout trip is scratched (they won’t commit themselves yet so neither would I on Oking them).

The first 11 seem alright to me, though Antonia Reeves and Robert Conchil weren’t on shakedown. The other two will have to commit themselves and $10 by next hiker meeting. I don’t really think 13 would be too many (+Sue? Is she going part?). Also Byron might go part with us. Que responde es? Shakedown was to Kern Peak with Wally Henry – an ickey trip, but it found a leader (I stayed home).

On food—I can get egg noodles and macaroni from the Wrangler cheep cheep cheep. All dehydrated, good for perhaps two meals on each 7 day segment. John Laine said any grits and he’ll wipe us both out (cream of wheat!). Will hold Y meeting and demand deposits, hand out medical slips and plan what support trips can be run. Powells volunteered their van for the shuffle, but with 13 people and packs it alone just won’t hack it. Drivers are you, Laine, the rest illegal. Don Shaw wants everyone to become Y members ($2) for insurance, so we probably should go along with that. I propose a s

plit group when we hit the N. Pal Sill area—with peak baggers and trail-o-phobes taking last years route. We can hassle that out on the trail.

Rob Culbertson was drafted into the Army and Kevin Anderson into the Treasury. They still mail bank notices to 2121. Its frustrating!. Kevin A’s parents are willing to drop off food—how about Primmer? Still in? Logistics are going to be interesting! Where do we keep the food that is to be taken up to us?

Boy, have you got problems

Mike

We decided to charge every one $50 each, for 28 days worth of food, plus gas for the transportation to the trailhead and back. We were all students and we were trying to keep it inexpensive, but that was ridiculous. If we had charged $100, we could have eaten a lot better. At the end of the trip, Mike and I were accused of profiteering by one hiker, because one guy thought he had paid top dollar ($50) but the food was crap.

I got out of school the week before we were to leave, and the week before the trip was when 95% of the work on the food was done. Our itinerary was planned and we already had out food drops in order. Of all the preparations I guess the food was the most work.

After the menu was made we had to buy enormous quantities of food, enough for 12 people for 27 days. These supplies purchased, we took over the facilities of the Palmdale Y for the week. The five or six steady workers became quite expert at food packing and accomplished the largest food packing in the history of the Y’s Hikers club, with no major problems. By Thursday our bundles were lined up along 3 ½ walls of the room, all in order and ready for the food drops. We had one big bag for each of the 3 cook groups, for each week. We would start out with one of the bags per cook group. They were bundled and stored in Mike’s bedroom, till they were picked up and delivered by our support parties, the Powells, the Peca’s, and Ken Primmer.

The concept of “hi-tech” in the early 70’s had a very different connotation than it does today with our access to GPS, cell phones, iPods, digital cameras, altimeter watches, LED head-lamps, Lithium-ion batteries etc. Our hike was just two years after man walked on the moon, so our idea of hi-tech electronics was pretty much limited to transistor radios and 8-track tape decks.

We used Ensolite closed-cell foam as a sleeping pad (a luxurious 3/8 inch of comfort), as there was no Thermarest or any other deluxe sleeping pad. Kevin had a Kelty half-torso, aqua-blue, inflatable mattress and pillow that, much to our surprise, lasted the entire trip without a leak. Down bags were (and still are) as good as it gets, but with limited tent technology, we always worried about getting them wet. For tents we mostly used a bright orange tube of plastic called a "tube tent," which was about 8 feet long, and when you strung the nylon twine between two trees, it formed a triangle with the floor being about 4 feet wide. Tube tents were a no-win proposition -- leave both ends open, and the rain blows in with the slightest breeze; button them up, and you get just as wet from the condensation. They at least had the virtue of being cheap and fairly light weight. We only strung up the tube tents the few times it threatened rain; otherwise, they were used as a large ground cloth to stake out your sleeping area and to keep your gear and cloths out of the dirt. Most nights we all slept out in the open, under the stars.

There were no internal-frame packs then, and many used the latest Kelty external-frame packs if they had the dough (model BB5?). Of course, these had to be purchased from Dick Kelty himself at his store on Victory Blvd. in Sun Valley (near Burbank) Calif. Kelty Packs brought to the main-stream the use of nylon material, aluminum frames, clevis pins, hold-open bars, divider compartments, mesh pack panel, padded shoulder straps, and a hipbelt consisting of a wide nylon strap (no padding) with a stainless-steel, quick-release buckle. It was a trick to keep the hipbelt from digging your Levi's pocket rivets into your hip bones, and your t-shirt often got pinched in the hipbelt buckle, eventually tearing a hole in it. I think the basic pack was around $25 and you could match it with a backpacker frame for $25 or a mountaineering frame for $28 with a bar that extended a few inches above the pack for lashing extra gear. The pack only came with 2 top side pockets but you could purchase 2 bottom side pockets and a large back pocket that was sewn onto the main body of the pack (if you look at the photos, you can see the various versions of the basic Kelty pack). These were "bombproof" packs that could comfortably carry a heavy load and that you knew would never fail. In 2016, Kevin Anderson still has, and sometimes uses, his 1971 Kelty pack that he took on this trip. Other members of the group used the venerable REI Cruiser, or other Kelty knock-offs.

Most of us had the classic waffle stomper boots, or all leather (and heavy) mountaineering boots with the Vibram-Lug sole. Someone had a lighter boot called the "John Muir Trail Boot." As they quickly started to show wear, we joked that they were good for exactly one trip on the JMT. I think most of us had cotton athletic socks worn under a heavy wool sock to absorb shock and wick moisture. Many had tennis shoes to wear around camp and Kevin had moccasins that were light and felt great after hiking all day.

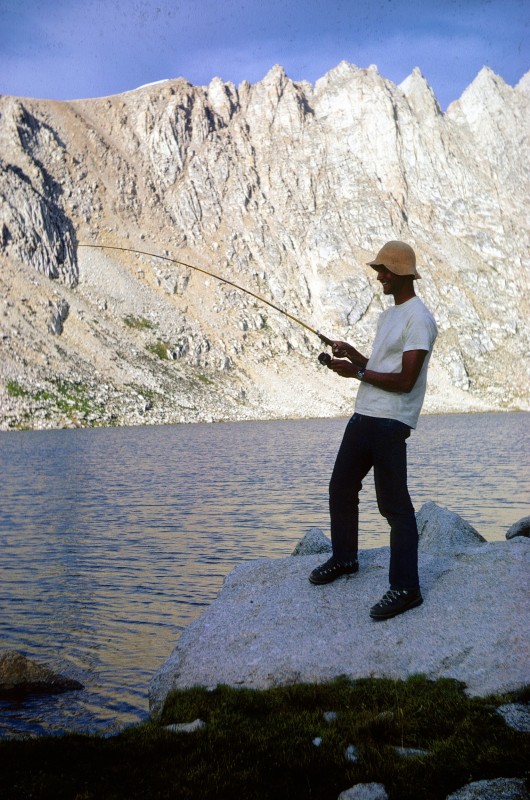

Navigation was done with topo maps, a compass, and we had one altimeter in the group-- GPS was more than 20 years in the future. I think we had one altimeter among the group because they were expensive, high precision instruments akin to a fine watch. They had to be constantly calibrated to a known altitude, which was most commonly done using the elevation of a lake posted on a topo map. Watches were analog, had to be wound daily, and only the expensive ones were truly waterproof, which is probably why most of us didn’t take one. As a result, we quickly acclimated to the natural timing of the rising and setting of the sun. Flashlights were heavy and batteries didn't last very long. I don't think anyone had any kind of night-time illumination except perhaps some candles. Everyone had a hat of some kind, but sunglasses seemed optional. We used sun-tan lotion, but I don't know how much it protected. We did get burned the first few days where we spent a good deal of time on snow pack getting over Donahue and Island Pass. After the first week, everyone was so tan that we never again burned, even on the high-altitude peaks. Cutter Insect Repellent in the form of a white cream with a distinctive smell was the best at the time, but it was no Deet. Cat-hole toilet hygiene was essentially the same except there were no alcohol-based hand sanitizers.

There were no polypro or other synthetic clothes, and I thought I was being very innovative to have a short sleeved nylon shirt to wear. Also popular were cotton fishnet shirts from Sweden that provided good circulation and could be layered with a t-shirt then a sweat shirt. Mostly we wore cotton t-shirts and sweat shirts with a wool, and windbreakers and wool long sleeve shirt. Levi, button-fly jeans were standard with cotton athletic shorts for hot weather and swimming. The cotton and wool worked well so long as you had a chance to dry it if it got wet. Most of us had a down coat, and for rain gear we had ponchos of coated nylon or just vinyl.

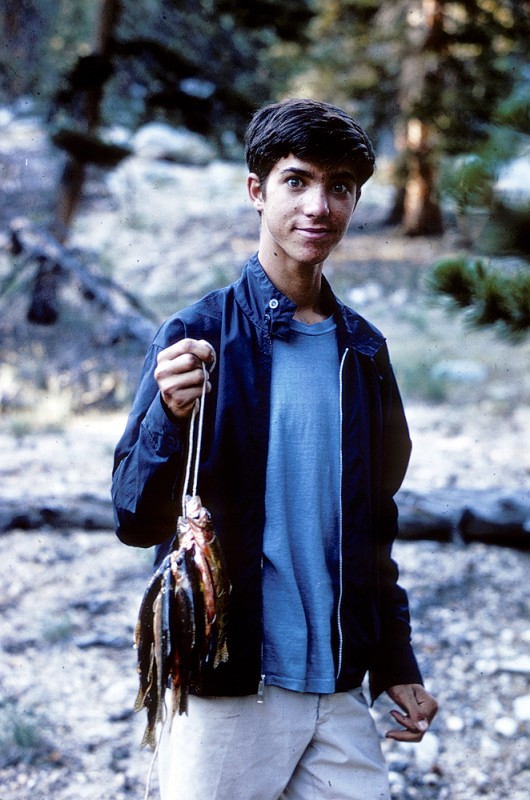

Being students, our food was the cheapest we could get, and Mike and I planned the food based on our experience with weekend backpacks. We didn’t reckon for bigger eaters than us, nor for a big increase in appetite which hit everyone after a week on the trail. We packed up all the food for 12 people for 28 days before we left, and a week’s worth of food was delivered to us at three trailheads along the way. In the menu plan below, A-1D = A (first week), 1D (first dinner). A1B = first week first breakfast, etc. This was crap food and we were hungry for a lot of the trip. Our fishing activities were absolutely necessary to augment our menu and especially our protein.

We didn’t routinely carry stoves but cooked over small fires. We used steel Army Ranger cooksets, one for each of the 3 cook groups of 4 people. These great cooksets had two nesting pots (that could be used a double-boiler), and a fry pan lid. We got pretty good at baking bread and biscuits and I recall using the double-boiler to melt Herseys bars mixed with powdered milk to make frosting for a cake. Each cook group had a small grill made of aluminum tubing that was carried in a cloth bag, and the pots were stored in a pillow case because they were filthy with soot. We didn’t use water filters in those days, and giardia was unheard of. The classic Sierra Cup, hung on a belt, was the status symbol of choice, but many used a Coleman plastic cup or a collapsible cup. Canteens usually held no more than 16 oz. with wide-mouth plastic bottles being popular. Drinking bladders were not needed because you simply dipped your cup or canteen as you hiked by the numerous streams and lakes along the JMT

We didn’t use bear canisters, we didn’t hang our food, and we never had a problem with bears. There were no permits, and I only saw one ranger on the whole 28 day trip. During the weekdays, between trailheads, we saw few other hikers. We didn’t do much training before the trip, and got in shape on the trail, but several of our party were runners by habit, or cross country team members, and everyone was pretty young. By the third week we were strong, and on the fourth week we were in superhuman shape. The notes that follow are from the journal I kept on the trip.